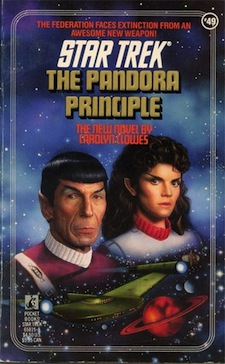

Remember Saavik? Saavik was a really cool character. I can’t remember when I saw Saavik’s official first appearance in the Star Trek canon, which was in The Wrath of Khan. But I do remember reading about her in Carolyn Clowes’ 1990 novel, The Pandora Principle, which is a ripping Girls’ Own Adventure yarn, in the style of Heinlein’s juvenilia. This came out when I was 14, and I probably bought it in the same year, which was definitely well before I saw The Search for Spock. I picked it up again because the plot involves Vulcan trafficking.

The other examples of Vulcan trafficking in my recent reading have focused on Romulan efforts to exploit Vulcans’ telepathic powers. The Romulans are alert to every possible advantage that could forward their political and diplomatic ambitions, and the Vulcans are surprisingly lackadaisical about looking for missing exploratory and trade vessels and keeping track of areas where such vessels tend to disappear.

Clowes’ Romulans are capturing Vulcan vessels near the Neutral Zone in order to use their crews as experimental subjects in chemical weapons tests on the planet Hellguard. Prison conditions on Hellguard appear to be improvisational, with little infrastructure on the planet’s surface and poor discipline among the Romulan guards. The result is widespread rape that creates a second generation of prisoners who wander the planet surface fighting for survival until rounded up by the guards to serve as test subjects. By the time the Vulcans arrive to rescue the prisoners and their children, the Romulans have apparently withdrawn, leaving a population of feral children. No Vulcan adults are found. Saavik—one of these children—impresses Spock by saving his life and looking at the stars.

The Vulcan rescue mission plans to send the children to a nice space station with lots of medical and educational staff, where they can heal from their rough start in life without upsetting anyone on Vulcan. Spock protests this plan on the children’s behalf. He argues that they deserve access to a planet and knowledge of their Vulcan relatives. He threatens to violate Vulcan social taboos surrounding matters of sex and reproduction by revealing the children’s existence and the details of their post-rescue placement to the Federation. Saavik is especially challenging to Vulcan social norms—she’s very attached to her knife—and Spock takes personal responsibility for her.

Saavik gradually recovers from her childhood trauma, and she gets to do a whole lot of cool stuff. When Spock is between missions, they live together and he answers all her questions. While he’s on missions, he sends her an endless stream of instructional tapes. He helps her get in to Starfleet Academy. Spock encourages Saavik to get to know humans and understand their culture—which she can hardly help doing in the dorms at Starfleet Academy, because her ears are really big. She learns to play baseball. She’s the kind of Mary Sue I love to read.

She’s visiting Spock on the Enterprise and doing adorably socially awkward things (like telling Uhura that she admires both Uhura’s personal appearance and her newly created ultra-secure code, which Saavik learned about from an instructional tape that Spock sent her—let’s take a minute to ask ourselves, does Spock understand the concept of an ultra-secure code?) when things go pear-shaped. Kirk is trapped in a vault under Federation Headquarters, the entire staff of which is dead. Saavik’s past holds the key to the mystery of the secret weapon that wipes out a whole city before the Enterprise can even take off for the Neutral Zone. It will take all of her fortitude, Spock’s guidance and teaching, Saavik’s baseball skills, and a significant quantity of dirt to solve these problems. Further assistance is provided by a mysterious alien who can fix anything. But the problems are solved, and everything is fine! A lot of people have died, but Clowes makes some strategic saves so that we, as readers, feel like all’s right with the world. Saavik is a hero. The Romulan conspiracy unravels.

Once The Pandora Principle ends, Saavik’s story takes a bizarre turn away from Heinlein’s juvenilia towards works like To Sail Beyond the Sunset. While I hadn’t seen The Search for Spock when I read The Pandora Principle for the first time, Carolyn Clowes certainly had—she refers to the film and to Vonda McIntyre’s novelization of it in her acknowledgments. That’s the film where, as several summaries delicately put it, Saavik “guides” the resurrected Spock through his first pon farr.

So this cool story about how awesome it is to be Spock’s protégé has, and since the moment of its creation had, a coda in which the pay-off for Spock’s tireless advocacy on behalf of the children of Hellguard and his work as Saavik’s mentor, is that Saavik is available to provide sexual services in a moment of crisis. I liked the story better when I didn’t know that.

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.